One Health Starts in Our Communities: Why Veterinary Clinics Matter More Than We Think

Life in Ila-Orangun Changed What I Thought I Knew About Public Health

When I moved to Ila-Orangun in March 2023 to begin my teaching position at the newly established Federal University of Health Sciences, I didn’t expect that dogs — not students — would alter my understanding of public health.

Until then, my connection to the town was mainly limited to festive visits: Christmas holidays, family gatherings, and quick trips home. Those visits were short and cautious, never letting me see the community as it truly is. Living here changed that.

Each day brought new discoveries — the rhythm of market days, the warmth of the people, and the surprising number of animals living freely among them. Goats, pigs, chickens, cats, and especially dogs. It didn’t take long before I noticed just how many dogs call Ila-Orangun home. Their presence seemed normal at first — part of the rural landscape — until I started thinking about what that means for diseases like rabies.

Rabies is Closer Than We Think

Ila-Orangun borders towns in Ekiti and Kwara States. In nearby Ekiti, canine rabies has been linked to between 7.1% and 27.3% of reported deaths (Mshelbwala et al., 2021). This single fact changed something in me. Suddenly, the sight of roaming dogs wasn’t just quaint — it was a warning of vulnerability.

During one of our community engagements, a man said to me, “Ifun okete ko lo n fa digbolugi. Obi tutu ti o ba ninu ifun re, to je mo, lon fa digbolugi,” translated as it is not the act of eating the African Giant Pouched Rat itself that causes the dog to become rabid, but because the African Giant Pouched Rat is known to eat kolanut. When the dog kills and eats the African Giant Pouched Rat, if the last kolanut eaten by the rat had not yet digested and the dog devours it along with the African Giant Pouched Rat, it can result in rabies in the dog.

That simple opinion revealed how deeply myths and misinformation influence people’s understanding of disease. It also showed how much progress we still need to make in including animal health in everyday discussions about public health.

Primary Healthcare Alone Isn’t Enough

Like most Nigerian towns, Ila-Orangun has Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) — 11 of them, one per ward. PHCs are essential: they treat malaria, deliver vaccines to children, and provide antenatal care. But when an animal bites someone, PHCs often cannot help because they lack rabies vaccines and depend on referral systems for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). The nearest tertiary hospital is in Osogbo, nearly 100 miles away. A round-trip costs about five U.S. dollars — more than many residents earn in a day. That’s just transportation, not including hospital fees or the multiple visits needed for rabies treatment.

A trader once told me,“By the time you go to Osogbo twice, you’ve spent your market money for the week.” For a disease that is 100% preventable with vaccination, the cost — financial, emotional, and physical —is heartbreaking.

“When communities understand, they act.”

We Need Veterinary Clinics in Every Town

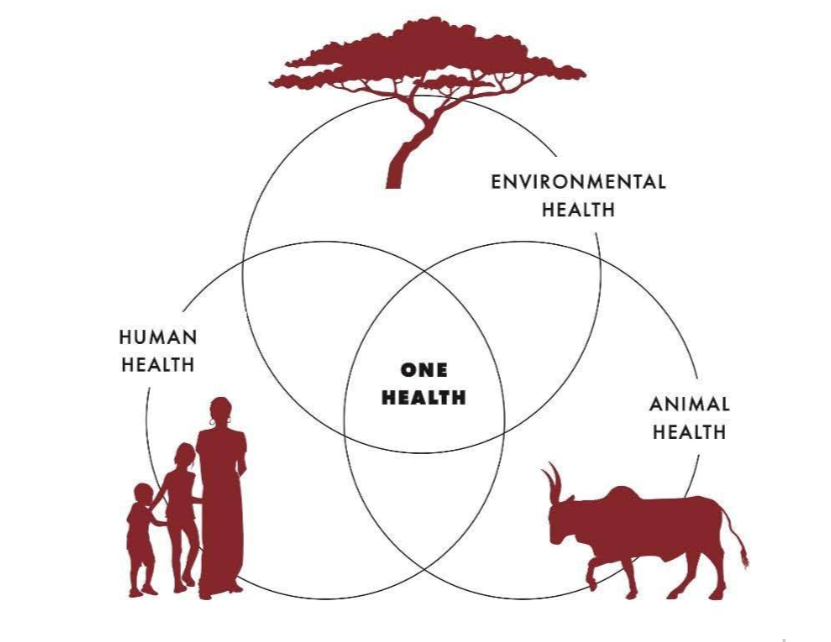

“Primary healthcare cannot stand alone — not in a country where over 70% of households interact with animals daily.” If Nigeria is serious about One Health — the concept that human, animal, and environmental health are linked — then every town needs at least one veterinary clinic, just as every ward has a PHC.

Zoonotic diseases like rabies, avian influenza, and even Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHFV) remind us that protecting human lives depends on safeguarding animal health. Having one veterinary clinic in each township could offer vaccination services, disease surveillance, outbreak response, and public education — all at a fraction of the cost of managing an outbreak after it occurs.

At the national level, we already have the structure. Nigeria’s Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security oversees veterinary boards, and our universities of agriculture and health sciences graduate hundreds of veterinarians each year. What we need is deployment — a strategic policy that ensures at least one veterinary professional is placed in every town, similar to Ogun State’s model, where veterinarians are stationed in abattoirs throughout the state.

A Lesson from Ila-Orangun

Through the Tetfund-sponsored Rabies Survey and the Nigeria Health Watch Rabies-Safe Ila-Orangun Project, our team has worked to educate residents about rabies transmission, bite management, and responsible dog ownership. We’ve met farmers who treat their dogs with goat medicines, households with multiple unvaccinated pets, and children who think rabies is caused by a dog eating the previous day’s pounded yams. Yet, we’ve also seen how quickly people embrace knowledge when it’s shared in ways that connect with their lives.

Health education, we’ve learned, is also social empowerment. It builds trust and transforms behaviour. When communities understand, they act.

A Practical Path Forward

Setting up a veterinary clinic in each township doesn’t mean starting from zero. Towns like Ila-Orangun already have access to human, animal, and environmental scientists through institutions such as the Federal University of Health Sciences. What’s needed is coordination — a consistent reporting and engagement channel between local and state authorities.

PHCs can also stock rabies vaccines alongside routine immunizations, especially in communities where hunting and animal rearing remain central to livelihoods. This integration is not just good policy — it’s life-saving.

There is also need for a language for rabies because every mad dog is not rabid and every rabid dog is not mad.

From Policy to Action

We don’t need to wait for September 28 — World Rabies Day — to prove our commitment to ending rabies. Each bite avoided, each dog vaccinated, and each child educated is a quiet victory for One Health. Every Nigerian deserves access to prevention. Every town deserves a veterinary clinic. If we act locally, we can prevent the next outbreak before it starts.

References

Mshelbwala, P.P., et al. (2021). Canine rabies epidemiology in Nigeria: Current status and future directions. Frontiers in Veterinary Science.