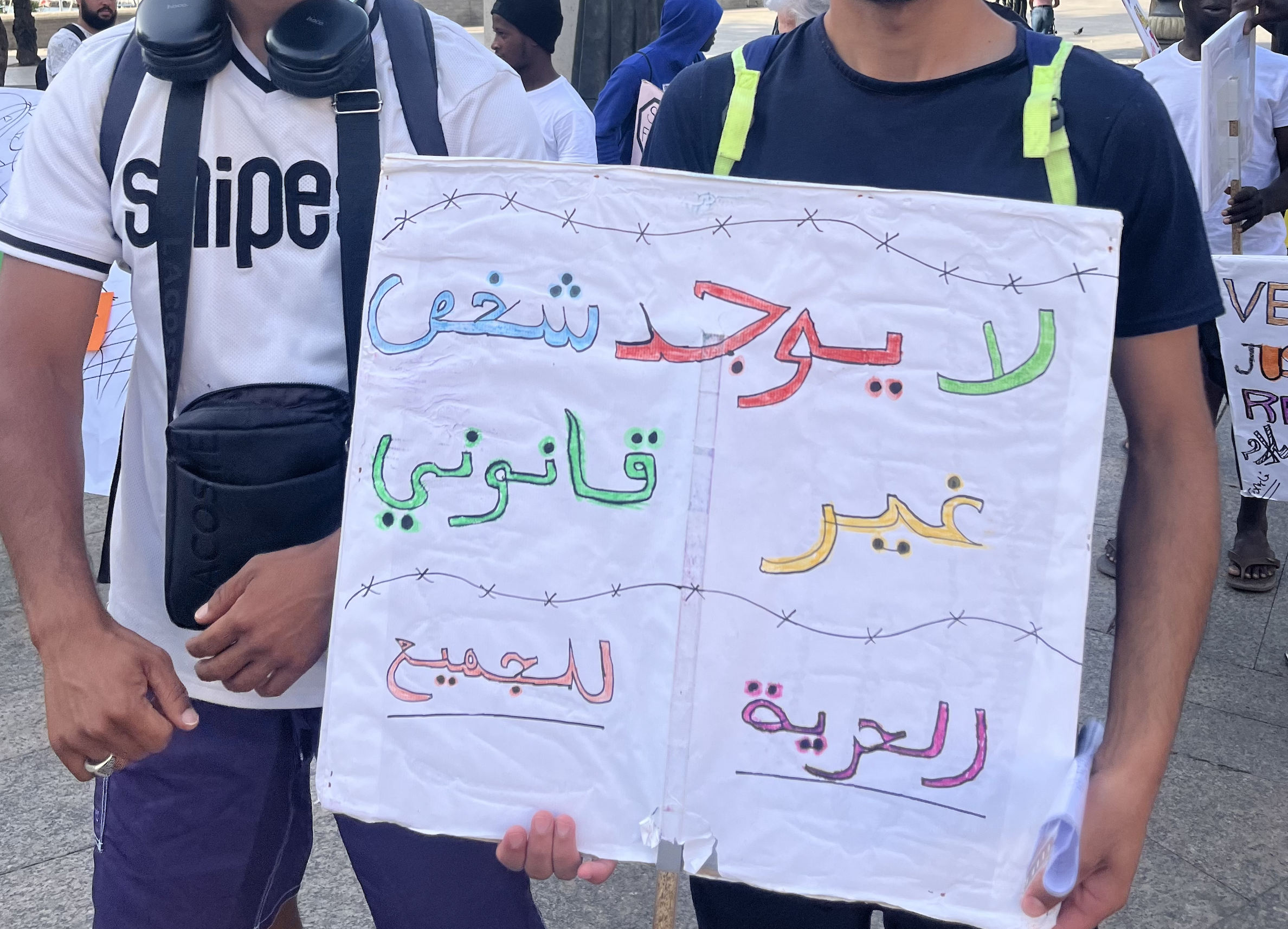

On the Margins of Europe: Mental Health, Substance Use, and Self-Harm Among Unaccompanied Minors in Ceuta, Spain

Bilal (15, Tétouan) was slumped on Ana’s shoulder in the University Hospital of Ceuta waiting room. His face was bruised and swollen from a fall. Ana and I, both volunteers with No Name Kitchen (NNK), had accompanied him there for medical care. For hours we sat, assuming he was just asleep. But when his name was finally called and he didn’t respond, we realized something was wrong: he wasn’t sleeping. He was unconscious. We eventually got him to his feet and into the exam room. He had been using hashish, Klonopin, and Lyrica all day.

This summer, I spent two months in Ceuta working with NNK, a grassroots organization that provides daily support to people on the move across European borders. I worked as Health Focal Point, offering first-line care: first aid, hygiene kits, and support accessing emergency services. What I witnessed went far beyond physical injuries. Harmful behaviors - daily drug use and self-harm - were common among unaccompanied minors, both inside and outside the protection system. As an epidemiologist, I was shaken by how routine rights violations in Ceuta map directly onto health outcomes, most visibly in the spiraling mental-health burden and erosion of wellbeing among these boys.

Unaccompanied Minors: Europe-Wide Harms, Ceuta’s Blind Spot

In context here, "harmful behaviors" is used to describe coping mechanisms these kids develop in response to extreme stress and systemic neglect. These include substance (ab)use (hashish, Lyrica, Roche, glue, etc.) and non-suicidal self-injury like cutting or burning. These behavioral patterns are not teen rebellion or experimentation, but rather, are rooted in survival.

Across Europe, there are growing (but still patchy) efforts to document the mental-health burden on unaccompanied minors (UAM). Small but consistent studies report high rates of PTSD (often 30–50%), alongside depression and anxiety affecting roughly a third or more. Reviews also suggest higher self-harm and substance use among unaccompanied vs. accompanied peers, with detention, discrimination, and isolation acting as drivers. Frontline workers in reception settings frequently flag substance use as a major or recurring concern.

By contrast, in Spain’s land-border enclaves - Ceuta and Melilla - there is almost no peer-reviewed research or routine monitoring on UAM mental health or harmful behaviors. Most of what we know comes from grassroots accompaniment (like NNK) and sporadic child-rights reporting. That invisibility has consequences: without data, services go under-resourced and harmful practices go unchecked.

Ceuta, a Spanish enclave surrounded by Morocco, is one of only two land borders between Africa and Europe. Every year, minors – mostly boys from Morocco - risk their lives swimming across to seek a better future. As of mid-2025, Ceuta was hosting 528 unaccompanied minors in a system meant to accommodate just 27. In July alone, over 50 minors swam ashore in a single day.

Once in Ceuta, most minors are stuck. They cannot legally leave for mainland Spain unless officially transferred. Many remain until they turn 18, living in overcrowded shelters or sleeping rough. Pushbacks (illegal expulsions) are still common, despite international condemnation. The city is segregated along ethnic and religious lines, and racism runs deep, both in institutions and in daily public life.

‘Care’ Inside the Centers for Minors

Most of the seven centers for minors in Ceuta are privately managed. UAM report harsh conditions daily, with those deemed "difficult" sent to stricter facilities. NNK spoke with Youssef, a former employee at these centers, who confirmed what many boys had already told us: they are hit by staff, verbally abused, ignored when hurt, and punished for simply reacting to trauma. Health provision is almost absent.

Years of cuts have hollowed out what little care existed. There are no full-time doctors in the centers, with “medical” tasks falling to untrained staff. “Workers hand out pills like antidepressants, antibiotics, pink anemia pills,” Youssef told us. “They’re not doctors. Mistakes happen.” Recently, local reporting indicated there was no psychiatrist in Ceuta; even before that, unaccompanied minors faced a nine-month wait just for an initial appointment. For boys living on the street, basic care often means the ER - if they make it there at all.

The system strips boys of control and punishes self-advocacy. Ayoub (16, Casablanca) swam to Ceuta after instability and family violence. His mother died when he was 14; he says the grief keeps him from sleeping, and he smokes weed to mute intrusive thoughts. When he helped organize peers to demand transport to mandatory training during a storm, the center director retaliated with a false report claiming he had skipped it. Speaking about a suicide attempt he witnessed inside a center, Ayoub said: “They get so angry because they have no control. That’s why they harm themselves.”

Image Viewer Discretion Advised: Healing and recent self-inflicted wounds on the arms of boys living on the street in Ceuta. These patterns of self-harm emerge as coping responses to chronic stress, violence, and systemic neglect. These are not marks of “ teenage rebellion,” but of survival.

Marginalization and Criminalization

These boys are marginalized at every level - as migrants, as minors, as Muslims, as racialized bodies, as unaccompanied youth. Spain’s anti-Moroccan racism, amplified by misinformation and far-right rhetoric (e.g., Vox), sets the tone. As Frantz Fanon wrote, colonialism is a “fertile purveyor for psychiatric hospitals”; Ceuta’s treatment of migrant minors is a colonial legacy that wounds both minds and bodies.

Ahmed (15, Tétouan) is one of them. Recruited into dealing at 12, he performs toughness to survive a city that pushed him onto the streets. Small for his age, he used to show his scars; now he asks for photos from “the other side”, the one without cuts. He says he stopped taking pills because they made him want to self-harm. “Now I only smoke weed,” he told us, proud of what feels like a safer choice.

For these boys, there is little art, sport, or space to process trauma. We saw shopkeepers shout them away when they were asking for some change. Even NNK’s psychosocial activities - basketball, swimming, haircuts, conversation - were routinely disrupted and policed. One afternoon, five officers arrived after neighbors complained. They didn’t stop the game; they just watched. The message was clear, and the boys left early and shaken.

Across Spain, street-involved migrant minors are systematically excluded from schools, youth centers, and community spaces. This exclusion - compounded by Islamophobia and racism - erodes protective factors, blocks recovery, and drives harmful coping. If we want different outcomes, access to safe public space and inclusive community programming must be guaranteed, not policed.

What Needs to Happen?

Summer acted as a pressure valve. When the heat arrived and the beaches filled, the rhythm changed. The boys could blend into crowds, claim space without instant suspicion, and spend long hours in the water - the same sea many had crossed - now a place to float, move, and breathe. In those weeks we saw fewer crisis episodes: less cutting, fewer heavy-use days, fewer ER visits. These means that context has the power to dial harm up or down.

That’s why we need routine, ethical monitoring of mental health and harmful behaviors in Ceuta and Melilla; year-round, low-threshold care that is trauma-informed and harm-reduction-based, with rapid referrals and safety planning; guaranteed access to stabilizers like sleep, food, recreation, and safe public space; enforceable child-rights protections that end pushbacks and ensure healthcare, education, and safe onward movement; and real state accountability so services are sustainably and publicly funded rather than patched together by overstretched NGOs (NNK is opening a small community space in Ceuta to help meet these needs and is seeking support to keep it running).

Grief, Rage, and the Need for Safe Places to Land

Bilal still talks about his father’s death when he’s high. His Instagram bio has the date, followed by a broken heart. Bilal is not a cautionary tale; he’s a teenager. He loves the rapper Morad, talks shyly about his crushes, and is quick to join any impromptu football match nearby. His story can still change.

As psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk writes in The Body Keeps the Score:

“Rage that has nowhere to go is redirected against the self, in the form of depression, self-hatred and self-destructive actions… Nothing feels safe - least of all your own body.”

This is the cost of chronic neglect - of borders that wound and institutions that abandon. It should move decision-makers, civil society, and communities to build places where this rage has somewhere to go - somewhere other than a child’s body.